The history of the Fillmore Town Theatre is ever evolving as new documentation is uncovered, but with the help of the Fillmore Historical Museum, Larry Holt of Sketchpad Graphic Design, and Fillmore citizens, here’s what we know so far!

The Fillmore Town Theatre was actually not the first theatre in Fillmore. Or maybe even the second.

There is some mention of a theatre called the Star at the south end of town. From the Fillmore Historical Museum: “The first real theater built in town was the Star Theater. It was built by Wilmer Akers in about 1900 in the 300 block of Fillmore St. It was a vaudeville house and silent movie palace. In 1902 Akers purchased a giant music box which played a 27” disc. That music box is still playing and can be heard at the Fillmore Historical Museum.”

The first theatre with a photo we have found so far is the Empire, a small theatre located (we think) in 359 Central Ave. As Fillmore began to grow, it became clear that a larger theatre needed to replace the approximately 187 seat Empire theatre.

Early Plans

Merton Barnes, a prominent citizen of Fillmore, is credited with the design of the new facility. It was modeled after a new theatre in San Fernando. Barnes had performed in cross country stock before moving to Ventura County, and managed the older Empire Theatre, where he staged local productions such as the Mikado and numerous minstrel shows.

Merton Barnes, a prominent citizen of Fillmore, is credited with the design of the new facility. It was modeled after a new theatre in San Fernando. Barnes had performed in cross country stock before moving to Ventura County, and managed the older Empire Theatre, where he staged local productions such as the Mikado and numerous minstrel shows.

Judge Merton Barnes acquired his judicial title from his sixteen years as Fillmore’s Justice of the Peace. In this capacity, he was, in 1924, elected Vice-President of the Magistrate and Constable Association of California. He moved his family from Ventura to Fillmore in 1911, opening the Empire theatre for motion pictures and traveling vaudeville.

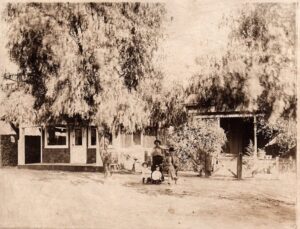

Leon B. Hammond, at the time a successful real estate investor, developed several buildings on the east side of Central Avenue. County of Ventura records show that Hammond and his successors traded in many properties in Fillmore. Hammond, an English army surgeon, moved to Fillmore with his wife, Trinidad, and reared three children, after adventures in Brazil, Mexico and New Orleans. Hammond built a home (pictured to the right) for his family in the heart of Fillmore on Central. The lure of development on Central soon necessitated moving the house, reportedly across an alley to the east.

Leon B. Hammond, at the time a successful real estate investor, developed several buildings on the east side of Central Avenue. County of Ventura records show that Hammond and his successors traded in many properties in Fillmore. Hammond, an English army surgeon, moved to Fillmore with his wife, Trinidad, and reared three children, after adventures in Brazil, Mexico and New Orleans. Hammond built a home (pictured to the right) for his family in the heart of Fillmore on Central. The lure of development on Central soon necessitated moving the house, reportedly across an alley to the east.

Merton Barnes and Leon Hammond would soon become connected to the parcel where the house once stood. According to a newspaper article in 1939 detailing the history of the theatre, Hammond began building a commercial building on his house property around 1915 and eventually transferred this asset to one George Alcock during the building’s construction. Mr. Hammond sadly lost much of his commercial property after being taken advantage of by a Los Angeles attorney, which may have precipitated the sale to Alcock.

Merton Barnes was willing to sign a long term lease with Alcock for the building but only if it became a theatre and only if it was built to his specifications. Those specs included a small stage, a large door at the rear to bring scenery through, a trap door on stage on stage for disappearing acts and a large screen on a flyaway system for moving pictures.

And so, the beginnings of the Fillmore Town Theatre began to take shape.

The Barnes Theatre

1916-1926

Charlie Chaplin wanna-bes, circa 1921, pose for a group photograph in front of the theatre during the days of silent films before the advent of talking pictures in 1927. The winning look alike, a long time Fillmore resident, stands in the front row, fifth from the right.

Charlie Chaplin wanna-bes, circa 1921, pose for a group photograph in front of the theatre during the days of silent films before the advent of talking pictures in 1927. The winning look alike, a long time Fillmore resident, stands in the front row, fifth from the right.

The Ventura Free Press reported that the new Barnes Theatre was, “easily the finest of its kind in this end of the state.” The most prominent feature of the building was a deep open lobby with a barrel vaulted ceiling opening to the street. The simple building front was decorated in patterns of two colors of brick and mortar. Stacked bond and rowlock courses gave visual strength to the piers flanking the lobby. A soldier course stood in a lintel at each of the two wide store front openings. A row lock arch, soldier course, and projecting header course combined to create a classical profile at the central arch. An elongated framed basketweave pattern was used to create a panel which relieves the flat expanse of running bond above each storefront. The parapet steps up over the arch, and the top two courses project to form a cornice.

Marble veneer in large panels finishes the bulkheads under the storefront windows, and is used as a skirt at the piers which flank the lobby opening; the luxurious finish prompted the Fillmore Herald to announce that “Nothing is too good for Fillmore.” 12 fixed reeded glass transom undivided, light metal frames with pivoting vent sash extend the length of each storefront opening.

A simple flat marquee signboard spanned the opening at the spring line with simple decoration; apparently, only surface illumination was used, as evidenced by a single goose neck lamp. The covered exterior lobby is deeper than the existing recessed foyer. Wall and vault are finished in plaster which may have been decoratively painted. Ceramic bases with colored lamps line the arch and frieze line of the side walls. Three poster frames are hung on each side wall from a continuous picture rail. Mrs. W. E. Cooney, a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago selected cream white and soft green for the lobby and theatre interiors.

There is not much written or photographic documentation of the theatre’s early appearance, so constructing an image of the theatre’s original appearance is based on receipts, newspaper articles and personal letters.

The deep outer lobby space left a wide but shallow foyer inside the front doors. The rear seats and top of aisles at the rear of the auditorium were separated from the foyer at the floor level by draw curtains.

The balcony and balcony stairs were added later, as was the stairway to the second floor. The upper level finished space consisted only of the existing projecting booth, though there is one reference to a manager’s office reached by a ladder. The auditorium was designed with a steep floor rake of two inches to the foot to insure good audience sight lines to the stage.

The original aisles were more closely spaced towards the center of the room than the existing layout. The original floor (which still exists under the later raised floor) stepped down to an orchestra pit which extended under the stage apron and opened to the basement by a door. An electric organ was added to the pit for musical accompaniment provided by local artists.

The original seats had stained wood backs; some were veneered, some had leather seats only, some had leather seats and backs, and the rear row “loge” seats were premium sized with leather upholstery. The side walls and ceiling of the auditorium have changed little in shape and detail. However, the original finishes were much finer than today’s flat finishes.

Opening night accounts refer to unfinished mural decorations. Initial historic color investigation shows that the auditorium walls were finished in several different colors. A dark tan punctuated the wainscot area below the wood trim. The wood trims were originally stained in walnut. The plaster walls above the wood trim were decorated in a architectural (simulated) stone finish. The painted texture was a wiped finish. The pilasters were finished with same false stone finish but in a slightly darker hue.

Each wall between the pilasters contained a painted decorative panel. The findings indicate that a Trompe-l’oeil painting technique was used (in stone tones) to represent bas-relief artwork. A decorative line of diamond shaped stencil art ran the entire length of the north and south walls. This embellishment was painted with a vivid red purple paint. The stage and loft of the theatre have changed very little except for the widening of the proscenium, addition of an exit ramp, and use of stage space for air handling equipment. The integrity of the wood-framed stage tower, fly loft, grid, fly gallery and pin rail has been maintained through lack of alteration and use since the 1920.

The Barnes Theatre was well prepared for presentations on opening night. A newspaper account reads:

“Manager Merton Barnes of the Empire Theatre has purchased from the Flag Scenic Co., of San Francisco, over a thousand dollars worth of scenery for the new theater which he expects to open October lst. Following is a list of the scenery included in the order, which is probably the largest individual order for scenery ever sold in Ventura county: One fancy drop curtain, two tormentors or wings, one garden set, one Olio drop, one street scene, four wood wings, a 9-piece interior parlor set, together with a grand drapery border and sky borders.”

The basement under the stage was originally reached by a door from the orchestra pit; the stage right stairway is an alteration. Dressing rooms, a hot air furnace, and independent lighting were provided.

A theatre is just a big empty building without engaging programming and Merton Barnes was very involved in what was featured in is new place.

As with The Empire, the Barnes Thetare was a multi-use facility. Besides motion pictures there were piano recitals, plays, public lectures and “Country Store” nights when groceries were given away at the movies. According to the paper, on November 2, 1917, high school students held a rally in front of the Barnes Theater to boost the Fillmore-Ventura football game to be held the next day. Afterward they were guests of Judge Barnes at the theatre. Mr. and Mrs. Richard Stephens hosted all the town’s children to a special Christmas movie, a tradition they had begun in 1912 at the Empire Theater.

Barnes’ community activities were close to his heart. He served as president of the Rotary Club, and of the Chamber of Commerce, acting also as Toast Master at many civic affairs. In 1921, the Ventura Elks Lodge #1430 was organized, and a number of Fillmore and Bardsdale men becoming Charter Members, some holding elective offices. Judge Barnes was one of these. he was chosen as one of the Lodge’s three Trustees. “Fortune Favored Fillmore” was his winning entry of the town’s slogan contest. Earlier, in Ventura, he had coined the still-used advertising slogan “Cash and Carry.” During World War I, he was head of the Fillmore Chapter of the American Red Cross.

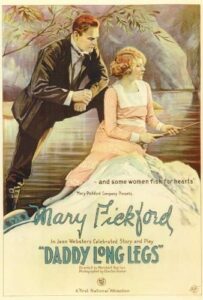

In 1919, the theater featured a “super attraction in 7 reels” (according to the ad). Mary Pickford’s “Daddy Long Legs”, produced and starring the world famous actress, was billed as “the Event of the Year”.

In 1919, the theater featured a “super attraction in 7 reels” (according to the ad). Mary Pickford’s “Daddy Long Legs”, produced and starring the world famous actress, was billed as “the Event of the Year”.

From Wikipedia:

Gladys Marie Smith (April 8, 1892 – May 29, 1979), known professionally as Mary Pickford, was a Canadian-American film actress and producer with a career that spanned five decades. A pioneer in the American film industry, she co-founded Pickford–Fairbanks Studios and United Artists, and was one of the 36 founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Cited as “America’s Sweetheart” during the silent film era,[4][5][6] and the “girl with the curls”,[she was one of the Canadian pioneers in early Hollywood and a significant figure in the development of film acting. She was one of the earliest stars to be billed under her own name, and was one of the most popular actresses of the 1910s and 1920s, earning the nickname “Queen of the Movies”. She is credited with having defined the ingénue type in cinema.

She was awarded the second Academy Award for Best Actress for her first sound film role in Coquette (1929), and she also received an Academy Honorary Award in 1976 in consideration of her contributions to American cinema. By the late 1920s Pickford’s career went into decline.

That’s a long explanation of why the Barnes Theater was so proud to feature her movie, “Daddy Long Legs.”

The 1920 Fire

A projector booth fire on September 21, 1920, caused no damage outside of the room. Merton Barnes purchased two new Powers 6B projectors to replace the damaged equipment. Metal lining in the projection booth partitions was credited with containing the fire.

The Stearns Theatre

1926-1931

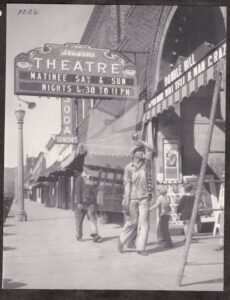

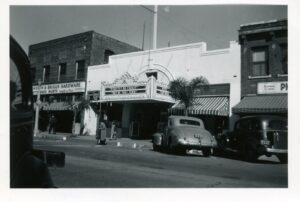

Mr. and Mrs. Henry C. Stearns bought the theater business from Barnes in 1926. Historic photographs from the 1920s show the addition of a blade marquee projecting over the sidewalk reading “Stearns Theatre.” The two-sided sign was attached to the building at the transom window level just north of the lobby entrance. In August 1928, Stearns repainted, changing the side wall panels of the auditorium to an unspecified new finish. At this time an evaporative cooling system was added.

Mr. and Mrs. Henry C. Stearns bought the theater business from Barnes in 1926. Historic photographs from the 1920s show the addition of a blade marquee projecting over the sidewalk reading “Stearns Theatre.” The two-sided sign was attached to the building at the transom window level just north of the lobby entrance. In August 1928, Stearns repainted, changing the side wall panels of the auditorium to an unspecified new finish. At this time an evaporative cooling system was added.

The Stearns’ major alteration to the building was the replacement in 1928, of earlier marquees with the currently existing square metal awning which covers the main entrance and forms an awning over the sidewalk. The change parallels the development of the movie house genre; the illuminated neon marquees of the movie palaces evolved during the 1920s to replace the sober signage of traditional theatre buildings. In the oft-quoted words of movie palace architect S. Charles Lee, “the show starts on the sidewalk.”

The Fillmore Harold reported in 1930, that, “a number of comfortable lounge seats had been built in the balcony.” This is the only documentation available other than field observation of construction materials and techniques to conclude that the balcony was added in 1930. Western Electric sound equipment for “talking pictures” was purchased late in 1930. This was probably the first sound system in the facility, since sound was introduced in 1927, and much larger theaters in metropolitan Los Angeles were just installing sound equipment as late as 1929.

The Fillmore Theatre

Scheinberg and Horwitz, 1931-1937

The Stearns leased the theatre in 1931, for a period of 10 years to Nate Scheinberg and Paul Horwitz of Van Nuys, CA (Fillmore Theatre Ltd.). The operation was closed for “extensive alterations and improvements in the interior” costing $350. Alterations included raising the floor near the stage (the existing floor, which is framed up from the original floor, over the orchestra pit), increased seating capacity and new loge-style cushioned seats, a better exit at the rear of the building (the ramp on the south side of the stage leading to the alley), a motor drive for the traveler curtain, new drapes and carpets, and painting of the walls to give a softer appearance. The new rear exit ramp undoubted replaced the now closed exit which opened through the south side wall to the rear of the adjacent building.

There is no explicit documentation to date the addition of the existing women’s lounge and manager’s office in the space west of the projection booth originally occupied by the lobby barrel vault. However, circumstantial evidence indicate that was not part of the 1931 remodel.

The 1931 redecorating was directed by Nate Smithe of West Coast Theatres. The West Coast Theatres house style was colorful and florid, leading to undocumented speculation that the remnants of decorative painting on the ceiling of the existing lobby may have been a part of this work. The free standing box office ticket kiosk in the outer lobby appears in a photograph dated c. 1940; however, no additional documentation of its provenance has been found.

The Fillmore Theatre

James Edwards, 1937-1939

In 1937, Scheinberg and Horwitz (Fillmore Theatres, Ltd.) assigned their lease from 1934 to 1944, to James Edwards (founder of Edwards Theaters), with the approval of the building owner at that time, the Fillmore Improvement Company. George Tighe, a prominent Fillmore citizen and businessman signed documents as President of the Fillmore Improvement Company. Edwards promptly engaged Robert E Powers Studios, a prominent theatrical decorative arts painter with studios in San Francisco and Los Angeles, for “Painting & Decorating” all of the interiors.

In 1937, Scheinberg and Horwitz (Fillmore Theatres, Ltd.) assigned their lease from 1934 to 1944, to James Edwards (founder of Edwards Theaters), with the approval of the building owner at that time, the Fillmore Improvement Company. George Tighe, a prominent Fillmore citizen and businessman signed documents as President of the Fillmore Improvement Company. Edwards promptly engaged Robert E Powers Studios, a prominent theatrical decorative arts painter with studios in San Francisco and Los Angeles, for “Painting & Decorating” all of the interiors.

Eventually, Edwards developed the prominent Edwards Cinema Circuit. It became one of California’s best-known and most popular theater chains, and by Edwards’ death in 1997, operated about 90 locations with 560 screens. Eventually, Edwards Theaters came under the Regal Theaters wings.

The 1939 Fire

Fire broke out in the balcony area of theater on January 12, 1939. Inventories, invoices and letters in James Edwards’s records document that the fire led to removal and replacement of substantially all fixtures, furnishings and equipment in the building. Seats were refurbished rather replaced. Carbon was found on the wood trim at the base of a pilaster on the side wall of the auditorium, indicating that the damage was extensive.

Fire broke out in the balcony area of theater on January 12, 1939. Inventories, invoices and letters in James Edwards’s records document that the fire led to removal and replacement of substantially all fixtures, furnishings and equipment in the building. Seats were refurbished rather replaced. Carbon was found on the wood trim at the base of a pilaster on the side wall of the auditorium, indicating that the damage was extensive.

Additional building alterations were undertaken in the winter of 1939. The State Fire Inspector required an additional exit in the rear, which is the existing ramp on the north side of the stage leading to the rear alley. Edwards requested the lessor to relocate the heater fan to the basement and omit a new furnace and cooling system in lieu of spending available funds for a new V-shaped marquee; it is observed on the site that Edwards received a new mechanical system and not a new marquee. A letter from the landlord to Edwards at this time requested that Edwards bring his architect to the site for suggestions as to how to locate the dressing room off the balcony. The evidence of alterations in this area suggests that the addition of the women’s toilet and manager’s office on the second level, and the stair leading to them, was completed in 1939. As late as 1937, the Power Studios painting invoice refers to a ladder leading to the manager’s office.

The Fillmore Theatre

Lloyd Beard, 1939-1953

Lloyd Beard signed an agreement to purchase James Edward’s lease on August 2, 1939; however, there is subsequent correspondence between Edwards and Minnie Minor at the Burbank Theatre concerning interest payments due on a note. A building permit was issued in 1945 for $6,500 for substantial structural and partition work. R. Wilson and George Dippel were listed as architect and contractor, respectively. The work included metal studs, 8″ I-beams, and a built up roof with slate surface. There is no existing evidence which fits this description. Another permit was issued in 1952, for alterations valued at $700 to a retail space, for David Wright Jr. by contractor L. V. Aslcren. This description corresponds to a men’s clothing store formerly located in the southerly store space.” A building permit was issued in March 1954, for entrance lobby change–doors etc., to Lloyd Beard and his contractor, Robert Johnson. In June 1954, the theatre advertised a “new wide screen,” which accounts for the removal of approximately 16″ of brick on each side of the proscenium opening.

Lloyd Beard signed an agreement to purchase James Edward’s lease on August 2, 1939; however, there is subsequent correspondence between Edwards and Minnie Minor at the Burbank Theatre concerning interest payments due on a note. A building permit was issued in 1945 for $6,500 for substantial structural and partition work. R. Wilson and George Dippel were listed as architect and contractor, respectively. The work included metal studs, 8″ I-beams, and a built up roof with slate surface. There is no existing evidence which fits this description. Another permit was issued in 1952, for alterations valued at $700 to a retail space, for David Wright Jr. by contractor L. V. Aslcren. This description corresponds to a men’s clothing store formerly located in the southerly store space.” A building permit was issued in March 1954, for entrance lobby change–doors etc., to Lloyd Beard and his contractor, Robert Johnson. In June 1954, the theatre advertised a “new wide screen,” which accounts for the removal of approximately 16″ of brick on each side of the proscenium opening.

The Fillmore Theater

Gordon West, 1953-1955; Harry Ulsh, 1955

Newspaper accounts report that Mr. & Mrs. Harry Ulsh took over from Gordon West as the owner and operator of the theatre in 1955. Residents recall that Mr. and Mrs. E. W. Zane operated the theatre in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Fillmore Towne Theatre

Dale F. and Marilyn J. Larson, 1971-1994

The theatre was transferred to the ownership of the Larsons in May, 1971, by Diana Hooper; Edith Beard, widow of Lloyd Beard, held a deed of trust at that time. Larson painted, reupholstered seats, re-carpeted, and replaced the drapery and projection screen, as well as removing a “fake front” at the entrance and installing new dado finish and trim at the entrance area. The acoustical material on the auditorium walls was added by a lessee, Harold Graves, some time after 1971.

The theatre was transferred to the ownership of the Larsons in May, 1971, by Diana Hooper; Edith Beard, widow of Lloyd Beard, held a deed of trust at that time. Larson painted, reupholstered seats, re-carpeted, and replaced the drapery and projection screen, as well as removing a “fake front” at the entrance and installing new dado finish and trim at the entrance area. The acoustical material on the auditorium walls was added by a lessee, Harold Graves, some time after 1971.

Field observation indicates that the wall, floor and ceiling finishes and concession stand and equipment in the lobby area can also be dated to this period. The existing marquee was restored in 1989, at a cost of more than $13,000 utilizing in part grants administered by the City of Fillmore for street front improvements. The Larson’s transferred the property to Keith D. and Susan C. Banks in 1990, who transferred it back to seller in 1992, in lieu of foreclosure.

1994 – Disaster

The Fillmore Towne Theatre was seriously damaged by the Northridge Earthquake on January 17, 1994. Portions of the unreinforced brick walls and parapets cracked, leaned and fell, causing city officials to quickly close the building. The desire to prevent demolition of this architecturally and culturally significant historic resource led to prompt action on the part of the citizens of Fillmore and government at the local and state level.

The Fillmore Towne Theatre was seriously damaged by the Northridge Earthquake on January 17, 1994. Portions of the unreinforced brick walls and parapets cracked, leaned and fell, causing city officials to quickly close the building. The desire to prevent demolition of this architecturally and culturally significant historic resource led to prompt action on the part of the citizens of Fillmore and government at the local and state level.

The city purchased the building for renovation. “Fillmore had been planning to renovate the downtown district by making improvements that mimicked the architectural style at the beginning of the century. After the quake, city officials added the restoration of the Central Avenue building to the wish list,” according to the Ventura County Star newspaper.

The foundation at the rear of the building had to be re-poured. Workers rebuilt the back wall with bricks from other crumbled Fillmore buildings and tin from an old barn. Great effort went into returning the theater to the way it was. The marquee and old light fixtures were saved and refurbished. Workers removed dressing rooms board by board, restored them and replaced them. Backstage walls are still covered with people’s names, dates and drawings.

At this point, the city took over the theater and did their best to run it. Unfortunately, despite a slate of first-run movies, the theater never made enough money to cover costs. After over a decade of annual losses, the city made the tough decision to close theater in 2011.

Several suitors looked at the theater, but a building with such a singular purpose was a hard sell. At one point, in 2020, one company considered buying the building but only to keep the facade. Their plan was to demolish the building from the facade back to the alley and build an apartment complex.

That deal expired on December 31, 2020. Desiring to return the theatre to a center of the arts for the residents of Fillmore, Mudturtle Theatrical, Inc., a nonprofit, was formed in 2021 to purchase theatre from the city. Escrow closed on November 12, 2021. Plans for renovation are underway and expected to be complete in the fall of 2023.